I read, as a practicing French Catholic, the encyclical ” Fratelli tutti “. Here is a brief analysis of it, as a compendium for those who would make the mistake of not reading it for themselves.

As I close the encyclical, a qualifier comes to me to sum it up: “ disturbing ”.

Its content really bothered me. I read there harsh criticisms on property, borders, immigration regulation, nation. I have surprised some whims or naivety there that seem extremely dangerous to a world-class leader concerning world brotherhood or the pacifism of Islam.

And then I remembered that the Holy Father has chosen to be the first pope to be named after the name of another disturbing, naive, crazy, illuminated character, Saint Francis.

So I agreed to be jostled by telling myself that I would surely have been very upset against this go-barefoot from Assisi if I had heard about him and his follies eight centuries ago. Go see the Sultan in the midst of the Crusades, when the Muslims had razed Jerusalem and waged a conquering (and victorious) war against the courageous Christian soldiers who sought to contain them. This ridiculous little monk, worth not mentioning, beggar in rags, who talks to the birds ? At most, an enlightened one, for sure. Nevertheless it is him that the Pope of that age had been dreaming of as the unique pilar that could prevent the Church from collapsing.

Pope Francis is not a leftist (sorry for those on the left who cry ” victory ! “) . He is not a rightist either (unlike those on the right that would dream of putting the pope on their side.)

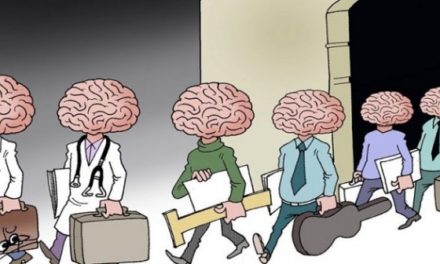

In this encyclical, Pope Francis just wants to remind all of us that we are, above all else, the children of God. And so brothers. And that this truth-too-often-lost-sight-of must irrigate our whole life, in the family, in couple, in our companies, our administrations, our political parties and our governments and even our international institutions.

He wants to remind us that we must distinguish what is normative – or in other words ” essential ” – from what is not. And that is what is ” disturbing “.

Let’s take the example of migrants. His purpose is to say that every man must be able to choose to go and settle where he wants. And that where one takes root, one will continue to improve the community in which he will establish himself, through his work, his creativity, his generosity, his lineage, etc.

But he is not saying – contrary to what some would have him say or dream of having read in his mouth – that migration flows as we experience it today are good things.

Indeed, he first denounce these countries and regimes that do not allow their people to live locally and that condemn their people to flee.

He dreams of voluntary migrants, but does not have any illusions about migrants forced by war, misery or arbitrariness.

He denounces economic models in which some have everything and others nothing.

He does not refuse private property, he simply said that we are servants of God in charge to grow its assets (see paragraphs 118 to 120) . Some have ten talents, others only one. Some manage them well, others badly. Some remain fraternal, others forget their humanity by concentrating exclusively on their ‘talents’, which they believe are their owns – big mistake.

Parable of the Good Samaritan

The Pope spends the whole of Chapter 2 studying on the Gospel of the Good Samaritan to remind us, again, what should be our priorities. He invites us not to look away from the sufferings in the world, and to spend our energy to alleviating them. He invites us to look at all men, including unbelievers or believers of other faiths.

It also invites us to act individually, without necessarily waiting for the intervention of States or public agencies.

He takes advantage of this encyclical to strongly reject slavery, nationalism and xenophobia as opposed to the principle of brotherhood of the children of God.

Welcoming societies

In chapter 3, Pope Francis invites communities to be open, so as not to become rigid and to be enriched by the contribution of others. The rules of the community must give pride of place to welcoming others because they are brothers in God. The whole encyclical recalls it, page after page : we are all brothers.

The Pope is not saying, however, that the rules of the welcoming community must be swept away by newcomers – read my lips. He also condemns universalism which standardizes while ignoring differences as much as stateless and wealthy cosmopolitans .

He points to a certain form of individualism which, under the guise of generous hospitality, in fact seeks only its advantage. Bringing in migrants to benefit from a low-skilled workforce and paying for it at a discount is not about fraternity, even under the guise of generosity.

Individualism does not make law, it creates ” partners ” whose purpose (hidden or denied) is to be ‘useful’, a horror in the eyes of the pope.

The pope also condemns liberalism (paragraphs 106 to 111) which says that everyone is free to live wherever he wants and as he wants but does not put in place any specific measures to help the poorest, the weakest, to enable them to fully integrate the society. He invites everyone, individuals and governments alike to put in place support measures for fragile or poor people.

He insists on the value of solidarity, both as a moral virtue, a social attitude and for its educational role. To serve is to take care of fragility (paragraph 115) and fight against the structural causes of poverty (inequalities, unemployment, absence of a homeland, impossibility of developing a home).

He also invites us to feel responsible for all human beings, including their country. A country or a regime that forces its nationals to flee is a problem to be solved for all other countries. We can very well read an invitation to international interference, as long as it does not mask a defense of personal (or state) interests under the guise of humanity.

There again, he invites the rich countries to have a particular option for the poor countries and points out, among other things, the weight of the debt in the capacity of certain poor countries to grow.

In chapter 4, Pope Francis reflects on the concrete consequences for countries of this little expression “ all brothers ”. This concerns migratory problems, but also the management of humanitarian crises : when they arise, we must be particularly generous to the people who are suffering.

He obviously invites supra-state responses and invites us to turn these chaos into opportunities for strengthened fraternities.

But the Pope also insists in this chapter (and precisely in this chapter entitled “ A heart opened to the world ”) on the importance of having roots, an identity, a love for the homeland, the people, his own culture because they are mandatory to really be welcoming. “ The good of the universe requires that each take care of his territory. ”

The reverse of this rootedness is the Tower of Babel, which God rejected and struck down.

Pope Francis continues his political approach in chapter 5 (“ The best policy ”) by recalling that the notion of people is legitimate, which he clearly distinguishes from populism and nationalism (which he rejects ). He even denounces the abuse of language which consists in accusing of populism all those who care for the people (paragraph 163).

The real political danger for Pope Francis is selfishness, concupiscence. He also rejects neoliberalism as such and stresses that the health crisis of COVID19 was a good reminder of the fragility of globalism.

The Pope places a lot of confidence in international organizations, in particular the UN and its various services, while recalling the Thomist principle of subsidiarity.

Pathways to find each other

In chapter 7 ” Pathways to find each other “, he invites men to benevolence, forgiveness, to always start from the truth, including to settle conflicts (and not the balance of power), going as far as utopian cry, ” Never again the war ” that Saint Francis would not have denied.

On several occasions he cites his meetings and his thinking with Sheikh Ahmed Al-Tayeb imam of the al-Azhar mosque in Egypt, which is a real spiritual reference in Sunni Islam (the most widespread). As such, Pope Francis fits perfectly into the approach of Saint Francis who wanted to establish a fraternal and in truth dialogue with the Muslim, in order to convert them.

In order to show to what extent fraternal dialogue and in truth should be a defining element for the years to come, the Pope ends his encyclical on the example of Saint Charles de Foucauld. This French priest, that never denied anything of what he was nor of his Faith, wanted to live as a brother among a Muslim people.

This encyclical is a wake-up call to make every person a brother for good and to draw all the consequences, whatever the cost.